This is a draft of a forthcoming article. As always, comments welcome.

John

The Webley-Fosbery Semiautomatic Revolver

(Click for larger view)

No, that’s not a misstatement or a contradiction in terms. Semiauto revolvers are indeed a fact, and have existed since the turn of the 20th Century! In 1895, British Lieutenant Colonel George Vincent Fosbery, holder of the Victoria Cross (Britain’s highest award for valor), conceived a workable mechanism for such a handgun.

Although his initial prototype was based on the Colt Single Action Army, he decided to work with the Webley & Scott Revolver and Arms Company, Ltd. to develop it further based on the Webley & Scott top-break revolver system. The W&S revolvers provided the quick extraction and easy loading ability that Fosbery wanted.

Fosbery’s concept was, in essence, splitting a revolver into two assemblies, the upper one being able to slide back on the lower frame through recoil. In doing so, the upper action-cylinder-barrel assembly, with a pivoting lever, cocks the hammer. A stud on the lower assembly guides external zig-zag grooves in the cylinder to rotate it ½ the distance to line up another chamber with the barrel. A spring returns the upper half to battery. In the process, the cylinder is then cammed the rest of the way to align a chamber into firing position. A short single-action pull on the trigger fires the round, and the process is repeated automatically until the gun is empty.

To eject the fired cases, pressing the lever to the left side of the hammer releases the barrel and cylinder assembly for pivoting. The barrel can then be manually hinged down smartly. The cylinder rises up around the pivot point with that motion, causing its internal ejector to be cammed out a certain distance. All the cases are ejected automatically when that is done, just as in the standard Webleys. The ejector then snaps back down into the cylinder. The chambers are all presented for reloading, and then the action is closed. To cock the hammer, it’s done manually or by pulling the entire upper assembly back and releasing it. Reloaded, the handgun can then be fired again.

Simply cocking the hammer or pulling the trigger does not rotate the cylinder, as in conventional revolvers. Only firing the piece or pulling the entire upper assembly back and letting it go accomplishes that. Normal make-ready procedure was to pull the upper assembly back and release it, ensuring that the gun was both cocked and the cylinder properly aligned. Standard practice when battle was imminent was to carry the gun fully cocked, with the manual safety lever on the left side of the handgun pushed upward. This cams the upper assembly a bit backwards, disconnecting the hammer from the sear and locking both the upper assembly and trigger in place. Pushing the safety down then instantly readies the gun for firing. The hammer must be fully cocked in order to engage the safety. The projecting part on the top strap is a spring-loaded stud that locks the cylinder in its proper place when the action is opened for reloading. It disengages when the barrel and cylinder assembly is returned to battery. When the action is open, the projecting part of the stud can be pressed to allow removal of the cylinder.

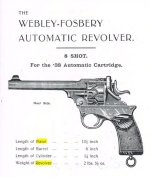

This new revolver was introduced at the Bisley pistol matches in July of 1900, and was subsequently offered for both military and civilian sales when full production began in 1901. Two standard calibers were offered. The most common was the .455 Webley, and the cylinders of these guns accommodated six rounds. British officers had to buy their own sidearms, and since the .455 was the required standard revolver round, it was natural enough that more of these were made. The second caliber was the .38 ACP round, then newly developed for early Colt semiautomatic pistols. With these, the cylinder would hold eight rounds, and a “full moon” clip was developed for quick reloading. The rear face of the cylinder was cut for these early clips to be utilized. It’s estimated that only about 200 .38 revolvers were ever sold. Officially, two types of .455 guns were made – initially, the 1901 model, and subsequently, the model of 1903. The .38 variation was called the model of 1902. A series of minor modifications resulted in six different designations, Marks I through VI. Total production of the automatic revolvers was about 4,200 (with some serial number block gaps resulting in serial numbers as high as around 4500) through the end of production in 1924. Remaining stocks were sold through the Webley catalog as late as 1939. Typical production rate had averaged out at about 10 guns per week. The more common .455 gun illustrated has the top strap marked "WEBLEY FOSBERY" on the left. The left side of the frame is marked with the winged bullet / ”W&S" trademark followed by "455 CORDITE.” All of these guns have scalloped barrels. Most have checkered hard rubber grips and a lanyard loop.

In 1902 and subsequently in 1907, the Webley-Fosbery was tested by the U.S. military. It did well in loading, accuracy and stopping power tests, but its tight tolerances and need for cleanliness and lubrication did not jibe with U.S. combat reliability needs. The pistol was also heavy – almost two and ¾ pounds. With the six-inch barrel, overall length was a long 11 inches. In the end, John Browning’s pistol design won out and became the famed Model 1911 .45 pistol.

Webley did offer the guns in other configurations if desired. In addition to the standard 6-inch barrel, one could buy a gun with either of the optional 4-inch or 7.5-inch barrels. Although a nickel finish could be had, apparently very few were shipped this way. Metford (polygonal) rifling and even .22 barrel inserts could be had on special order. The longest barrel was available with sights more suitable for target work. At the time, the pistol was fairly popular as a competition gun, with its easy trigger pull and no need to cock the hammer. In 1902, famed target shooter Walter Winans fired 12 shots (including a reload) into a 2-inch group at 20 yards in just 20 seconds. Rapid reloading was accomplished through the use of a Prideaux speedloader.

In war, the Webley-Fosbery was never adopted by any government officially. It did see some action in the second Boer War and World War I, where British infantry officers often carried privately-purchased examples. English pilots sometimes used them in the air before machine guns were prevalent – there were no ejected shells to cause problems. They were comparatively heavy and unwieldy, factors which plagued them. They were also susceptible to jamming from dust, mud and battle debris. A stout hold was required for the action to cycle reliably. Cocking them by manually cycling the whole upper half was a bit of a pain. This gun wasn’t simple to operate, and required the owner to be fully familiar with its peculiarities. It was interesting, had some advantages, and a few serious shortcomings.

The Webley-Fosbery was somewhat notable on the silver screen, appearing in such movies as The Maltese Falcon (1941) and Zardoz (1974). Wherever shown, it was easy enough to spot with its zig-zag cylinder being immediately noticeable. It had a certain exotic mystique, and although it has become quite recognizable, few have actually seen or handled one in person. It was, sadly, the answer to an unasked question. Normal semiauto pistols and normal revolvers served quite well then, and quite well now.

As far as collector value is concerned – well, if you want one, grab your checkbook and prepare to drain your IRA account. The .455 versions will probably cost you multiple thousands, and the .38 types are virtually unobtainable, worth quite a bit more when and if found. These are innovative, fascinating and collectible handguns, classic in every sense of the word – but darn expensive.

(c) 2019 JLM

John

The Webley-Fosbery Semiautomatic Revolver

(Click for larger view)

No, that’s not a misstatement or a contradiction in terms. Semiauto revolvers are indeed a fact, and have existed since the turn of the 20th Century! In 1895, British Lieutenant Colonel George Vincent Fosbery, holder of the Victoria Cross (Britain’s highest award for valor), conceived a workable mechanism for such a handgun.

Although his initial prototype was based on the Colt Single Action Army, he decided to work with the Webley & Scott Revolver and Arms Company, Ltd. to develop it further based on the Webley & Scott top-break revolver system. The W&S revolvers provided the quick extraction and easy loading ability that Fosbery wanted.

Fosbery’s concept was, in essence, splitting a revolver into two assemblies, the upper one being able to slide back on the lower frame through recoil. In doing so, the upper action-cylinder-barrel assembly, with a pivoting lever, cocks the hammer. A stud on the lower assembly guides external zig-zag grooves in the cylinder to rotate it ½ the distance to line up another chamber with the barrel. A spring returns the upper half to battery. In the process, the cylinder is then cammed the rest of the way to align a chamber into firing position. A short single-action pull on the trigger fires the round, and the process is repeated automatically until the gun is empty.

To eject the fired cases, pressing the lever to the left side of the hammer releases the barrel and cylinder assembly for pivoting. The barrel can then be manually hinged down smartly. The cylinder rises up around the pivot point with that motion, causing its internal ejector to be cammed out a certain distance. All the cases are ejected automatically when that is done, just as in the standard Webleys. The ejector then snaps back down into the cylinder. The chambers are all presented for reloading, and then the action is closed. To cock the hammer, it’s done manually or by pulling the entire upper assembly back and releasing it. Reloaded, the handgun can then be fired again.

Simply cocking the hammer or pulling the trigger does not rotate the cylinder, as in conventional revolvers. Only firing the piece or pulling the entire upper assembly back and letting it go accomplishes that. Normal make-ready procedure was to pull the upper assembly back and release it, ensuring that the gun was both cocked and the cylinder properly aligned. Standard practice when battle was imminent was to carry the gun fully cocked, with the manual safety lever on the left side of the handgun pushed upward. This cams the upper assembly a bit backwards, disconnecting the hammer from the sear and locking both the upper assembly and trigger in place. Pushing the safety down then instantly readies the gun for firing. The hammer must be fully cocked in order to engage the safety. The projecting part on the top strap is a spring-loaded stud that locks the cylinder in its proper place when the action is opened for reloading. It disengages when the barrel and cylinder assembly is returned to battery. When the action is open, the projecting part of the stud can be pressed to allow removal of the cylinder.

This new revolver was introduced at the Bisley pistol matches in July of 1900, and was subsequently offered for both military and civilian sales when full production began in 1901. Two standard calibers were offered. The most common was the .455 Webley, and the cylinders of these guns accommodated six rounds. British officers had to buy their own sidearms, and since the .455 was the required standard revolver round, it was natural enough that more of these were made. The second caliber was the .38 ACP round, then newly developed for early Colt semiautomatic pistols. With these, the cylinder would hold eight rounds, and a “full moon” clip was developed for quick reloading. The rear face of the cylinder was cut for these early clips to be utilized. It’s estimated that only about 200 .38 revolvers were ever sold. Officially, two types of .455 guns were made – initially, the 1901 model, and subsequently, the model of 1903. The .38 variation was called the model of 1902. A series of minor modifications resulted in six different designations, Marks I through VI. Total production of the automatic revolvers was about 4,200 (with some serial number block gaps resulting in serial numbers as high as around 4500) through the end of production in 1924. Remaining stocks were sold through the Webley catalog as late as 1939. Typical production rate had averaged out at about 10 guns per week. The more common .455 gun illustrated has the top strap marked "WEBLEY FOSBERY" on the left. The left side of the frame is marked with the winged bullet / ”W&S" trademark followed by "455 CORDITE.” All of these guns have scalloped barrels. Most have checkered hard rubber grips and a lanyard loop.

In 1902 and subsequently in 1907, the Webley-Fosbery was tested by the U.S. military. It did well in loading, accuracy and stopping power tests, but its tight tolerances and need for cleanliness and lubrication did not jibe with U.S. combat reliability needs. The pistol was also heavy – almost two and ¾ pounds. With the six-inch barrel, overall length was a long 11 inches. In the end, John Browning’s pistol design won out and became the famed Model 1911 .45 pistol.

Webley did offer the guns in other configurations if desired. In addition to the standard 6-inch barrel, one could buy a gun with either of the optional 4-inch or 7.5-inch barrels. Although a nickel finish could be had, apparently very few were shipped this way. Metford (polygonal) rifling and even .22 barrel inserts could be had on special order. The longest barrel was available with sights more suitable for target work. At the time, the pistol was fairly popular as a competition gun, with its easy trigger pull and no need to cock the hammer. In 1902, famed target shooter Walter Winans fired 12 shots (including a reload) into a 2-inch group at 20 yards in just 20 seconds. Rapid reloading was accomplished through the use of a Prideaux speedloader.

In war, the Webley-Fosbery was never adopted by any government officially. It did see some action in the second Boer War and World War I, where British infantry officers often carried privately-purchased examples. English pilots sometimes used them in the air before machine guns were prevalent – there were no ejected shells to cause problems. They were comparatively heavy and unwieldy, factors which plagued them. They were also susceptible to jamming from dust, mud and battle debris. A stout hold was required for the action to cycle reliably. Cocking them by manually cycling the whole upper half was a bit of a pain. This gun wasn’t simple to operate, and required the owner to be fully familiar with its peculiarities. It was interesting, had some advantages, and a few serious shortcomings.

The Webley-Fosbery was somewhat notable on the silver screen, appearing in such movies as The Maltese Falcon (1941) and Zardoz (1974). Wherever shown, it was easy enough to spot with its zig-zag cylinder being immediately noticeable. It had a certain exotic mystique, and although it has become quite recognizable, few have actually seen or handled one in person. It was, sadly, the answer to an unasked question. Normal semiauto pistols and normal revolvers served quite well then, and quite well now.

As far as collector value is concerned – well, if you want one, grab your checkbook and prepare to drain your IRA account. The .455 versions will probably cost you multiple thousands, and the .38 types are virtually unobtainable, worth quite a bit more when and if found. These are innovative, fascinating and collectible handguns, classic in every sense of the word – but darn expensive.

(c) 2019 JLM

Last edited: