Hope you'll find the following interesting - a bit of firearms history from the "Great War" era.

John

When the United States entered World War I (then known as “the Great War”) in 1917, the quest developed for more effective weapons with which to conduct trench warfare. It was felt that a high-capacity semiauto rifle firing a smaller reduced-power cartridge would be valuable. The standard .30-06 cartridge used in rifles and machine guns was unnecessarily powerful for close work in the trenches, and the manually-operated bolt rifles were slow and awkward to operate.

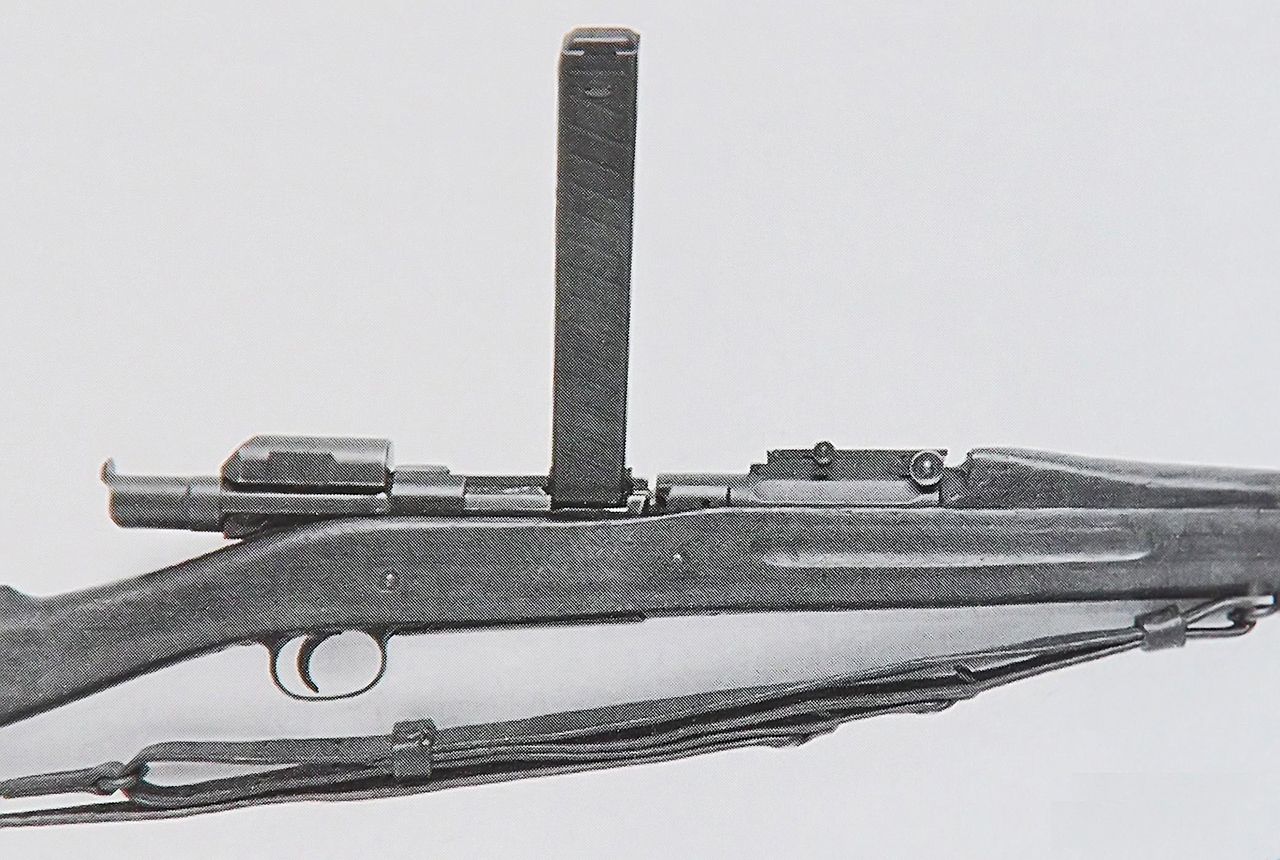

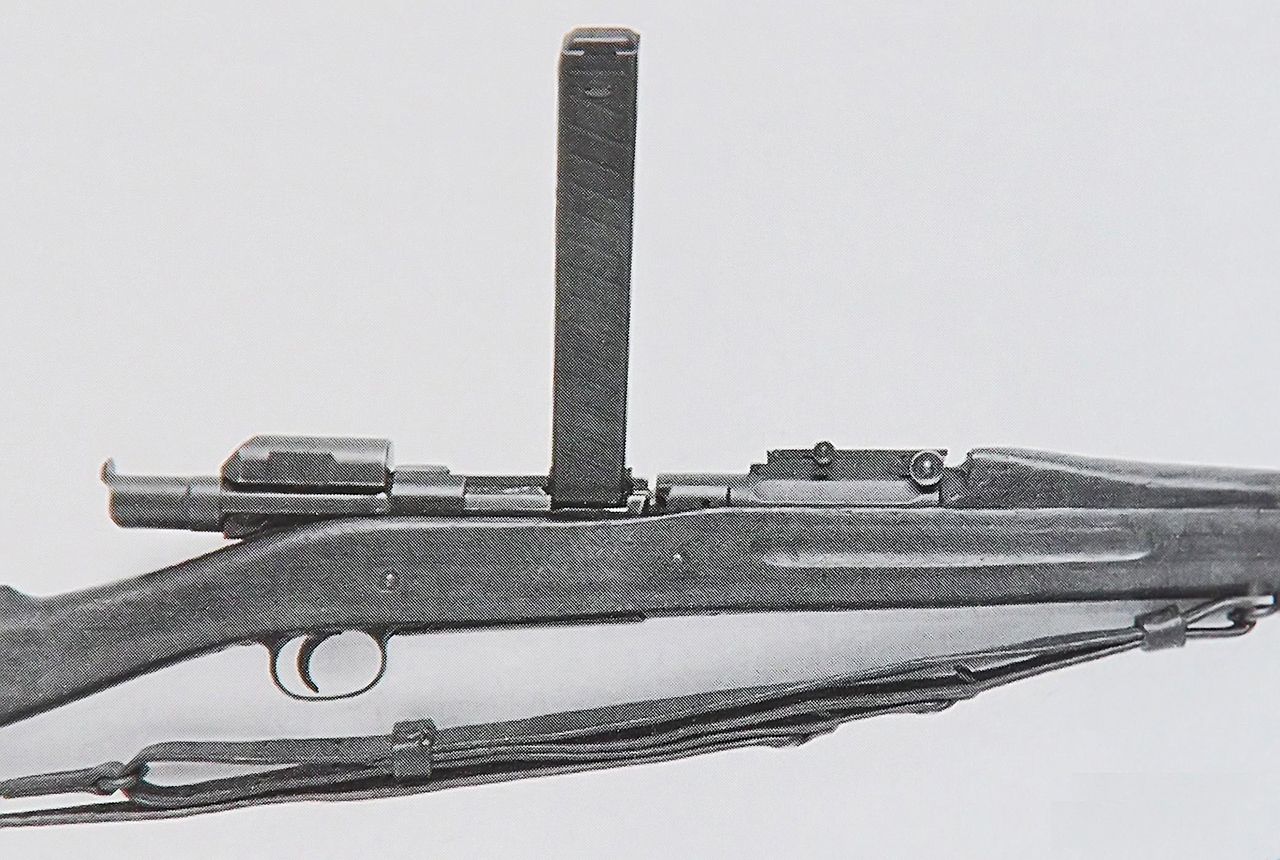

John Douglas Pedersen, a talented designer who was then working for the Remington-Universal Metallic Cartridge Company in Bridgeport, Connecticut, set about to work on that challenge. The solution he came up with was quite innovative. In the summer of 1917, he requested a secret demonstration of what he had developed for the Army Ordnance Department. Given Pedersen’s sterling reputation for design work, his request was granted and a demonstration was conducted on October 8, 1917. Present were General William Crozier (the Army Chief of Ordnance), and a select few Congressmen, all of whom had been sworn to secrecy. What they saw on that day was revolutionary. Pedersen began the demonstration by firing what appeared to be a standard Model 1903 rifle, operating the bolt normally. After he fired a few shots, he quickly removed the bolt and dropped it into a special pouch attached to his belt. He then produced a strange, longish device from a scabbard on his belt, inserted it into the bolt raceway in the rifle, and latched it in place using the magazine cutoff thumbpiece on the rifle. Then he snapped a magazine holding forty pistol-sized .30 caliber cartridges into the device. This projected at an angle to the right of the rifle, allowing use of the standard sights. He then charged the device by pulling and releasing a heavy spring-loaded block on the back of it. He quickly proceeded to fire 40 shots as fast as he could pull the trigger.

The witnesses to this event were incredibly impressed, and the potential for the use of this invention in trench warfare was immediately recognized. Pederson called it an “automatic bolt” but almost immediately it became known as the Pedersen Device. It operated pretty much like a semiautomatic blowback pistol, but its framework was a slightly-altered Model 1903 rifle. The barrel of the device, which inserted into the chamber, was configured to the dimensions of the standard .30-06 cartridge case, and the small .30-caliber cartridge chambered in the breech of that barrel. This barrel within a barrel was rifled to start the bullet spinning down the regular rifled tube of the rifle. The rifle itself was slightly altered. It had an ejection port cut into the left side of the receiver, and the trigger mechanism was modified to allow both semiautomatic firing and the release of the firing mechanism in the standard bolt. The magazine was secured in place by two spring-loaded catches.

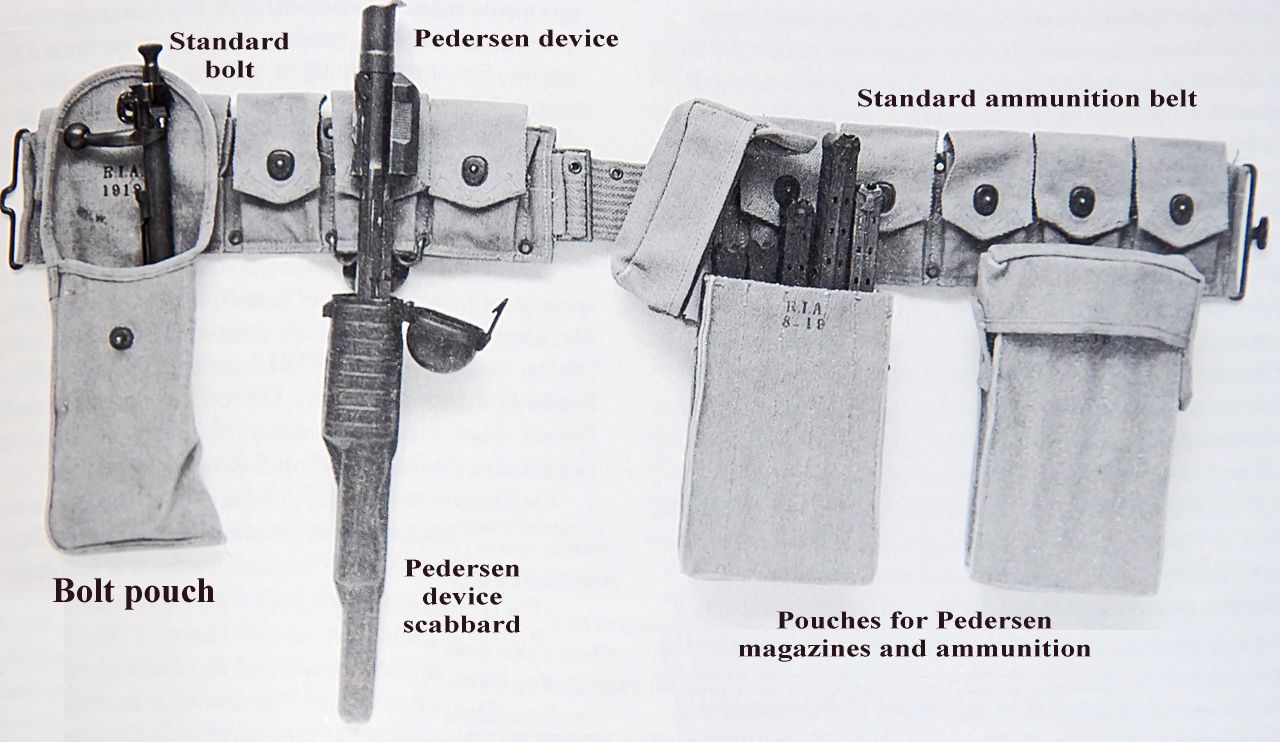

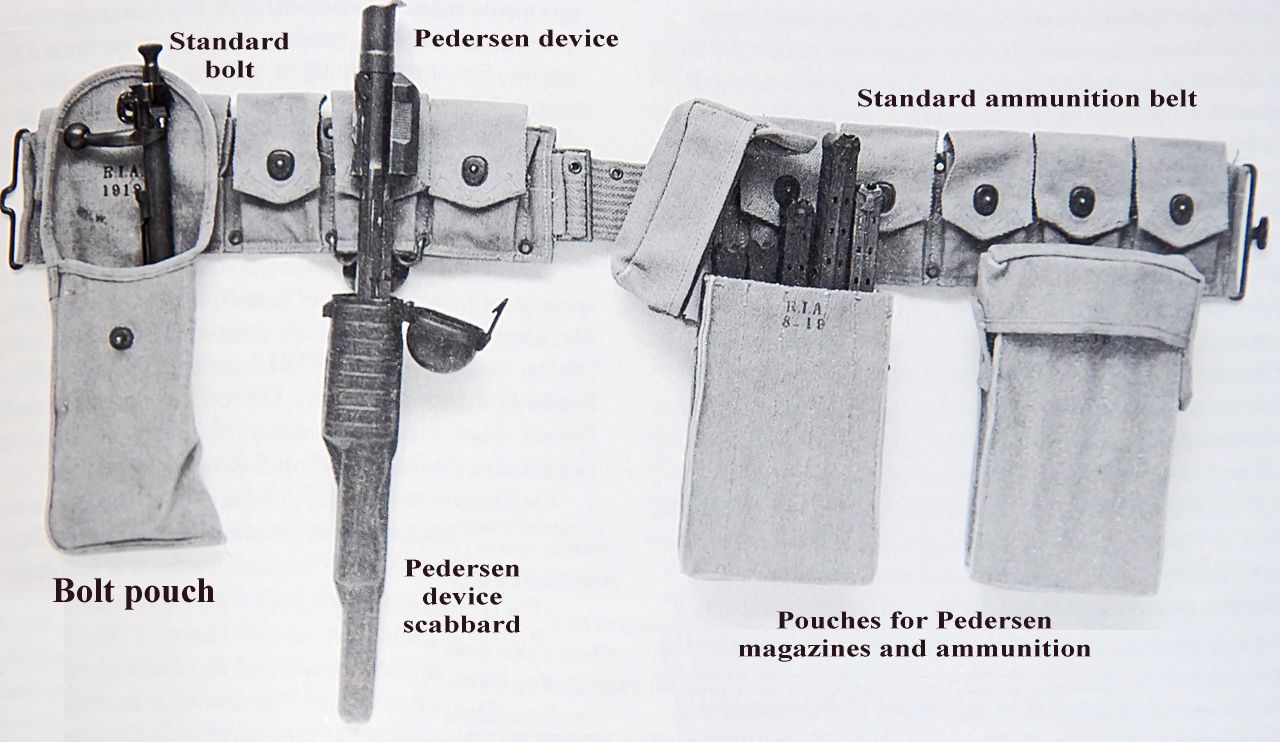

While the cartridges used were similar to .32 ACP pistol rounds, the bullets were .30 caliber, full metal jacketed, and weighed 80 grains. A charge of 3.5 grains of smokeless powder propelled the projectile at approximately 1300 feet per second, resulting in a muzzle energy of about 300 foot-pounds. That doesn’t sound like much, but being fired from a 24-inch barrel, it was way more powerful than similar rounds fired from a pistol. The device itself was carried on the belt in a special metal scabbard with belt hooks, and a web pouch was provided for the standard bolt when removed from the rifle. Two canvas magazine pouches held five magazines each, allowing a basic load of 400 rounds to be carried on the person. Each loaded magazine weighed about a pound, and the device itself weighed a little over two pounds. With rifles using these devices the trenches could easily be dominated with withering fire.

In November of 1917, a sample of the device was delivered by Captain J.C. Beatty to General John Pershing, the U.S. Army Expeditionary Force commander in France. Beatty was sworn to secrecy on the project; it was all classified as Top Secret. On December 9 of that year, General Pershing convened a board consisting of Capt. Beatty and four senior Ordnance officers. They tested the device for rate of fire, accuracy, penetration and reliability. Pershing was so impressed with the results of this test that he sent a memo to the Chief of Ordnance recommending an initial purchase of 100,000 of the devices and 5,000 rounds of ammunition per gun, providing a daily supply of 100 rounds per gun. He strongly believed it would do wonders for their efforts in France. Another memo soon followed, which stated “Desire 25,000 Pedersen attachments to be held in reserve. Replacements 50% per year on devices, and 200% on magazines. Request 40 magazines be shipped with each device. When will shipments be made? -Pershing.” Pershing was anticipating a huge offensive push in the spring of 1919, and wanted lots of these devices.

Because of its Top Secret classification, the device was given the intentionally misleading name of “Automatic Pistol, Caliber .30, Model of 1918, Mark I.” The ammo boxes were marked “40 – CAL. 30 AUTO, PISTOL / BALL CARTRIDGES / MODEL OF 1918” All the ammunition was produced by Remington-UMC, and so marked on the boxes. The production of this ammo caused some speculation and dismay in the press that the armed services were now using some sort of pipsqueak pistol to replace our Model 1911 .45 ACP handgun!

The eventual order placed with Remington was for 133,450 devices, and a contract was let for 800 million cartridges. These would be packed 40 to a box, each box enough to fill one magazine. Rock Island Arsenal produced the pouches for the bolt and magazines, and Graham Manufacturing Company made the scabbards for the device. Springfield Armory began manufacture of the modified ’03 rifle, which was dubbed the “U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, Model of 1903 Mark I.” As stated, the major differences from the regular ’03 were the ejection port, the trigger mechanism, the cutoff latch, and a stock relieved under the ejection port. Production of these rifles began in December 1918 and continued until March, 1920. 97,520 Mark I rifles were made, with serial numbers running from 933045 to 1186358. Most were finished in black Parkerizing, which had become the military standard.

World War I ended before any of the devices could be used in the war. A less hurried and more critical examination of the scheme revealed that the round was indeed quite underpowered, the equipment and ammo was heavy, and the potential for loss of the device and/or the bolt in the heat of battle was high. Some were actually used for gallery rifle practice and consideration was given to keeping them in reserve for riot control, but in April, 1931, an order was given to destroy all the devices and their accoutrements. Most were completely ruined in bonfires and then deep-sixed. A very few were stolen or salvaged to become incredibly expensive collector items today. Estimates vary on the number of surviving examples from a few dozen to as many as 100. The scabbards are even scarcer. The bolt and magazine pouches occasionally surface, but are fairly rare. A few “Mark II” devices, perhaps less than six, for the Model 1917 “Enfield” rifle are known. The Mark I rifles were almost all re-converted to standard ’03 specifications, and only a small number now remain in original device-ready condition. I’m fortunate enough to own one of these which left Springfield Armory in November of 1919. Today, a lot of people wonder about the hole in the side of the receiver when they encounter one, and the story behind that hole is still not widely known.

The Pedersen device was innovative, but became a dead end in firearms history. The devices and the rifles that used them are now very desirable classics. Few can afford one of the devices when and if one rarely becomes available on the collector market. The Mark I rifles can still be found here and there in varying conditions of originality. While not cheap, they’re considerably less expensive then the few remaining devices. There is a lot of history behind them.

(c) 2012 JLM

A pic of John D. Pedersen:

Some shots of the device and its ammo and accoutrements:

My own Mark I Springfield rifle:

John

When the United States entered World War I (then known as “the Great War”) in 1917, the quest developed for more effective weapons with which to conduct trench warfare. It was felt that a high-capacity semiauto rifle firing a smaller reduced-power cartridge would be valuable. The standard .30-06 cartridge used in rifles and machine guns was unnecessarily powerful for close work in the trenches, and the manually-operated bolt rifles were slow and awkward to operate.

John Douglas Pedersen, a talented designer who was then working for the Remington-Universal Metallic Cartridge Company in Bridgeport, Connecticut, set about to work on that challenge. The solution he came up with was quite innovative. In the summer of 1917, he requested a secret demonstration of what he had developed for the Army Ordnance Department. Given Pedersen’s sterling reputation for design work, his request was granted and a demonstration was conducted on October 8, 1917. Present were General William Crozier (the Army Chief of Ordnance), and a select few Congressmen, all of whom had been sworn to secrecy. What they saw on that day was revolutionary. Pedersen began the demonstration by firing what appeared to be a standard Model 1903 rifle, operating the bolt normally. After he fired a few shots, he quickly removed the bolt and dropped it into a special pouch attached to his belt. He then produced a strange, longish device from a scabbard on his belt, inserted it into the bolt raceway in the rifle, and latched it in place using the magazine cutoff thumbpiece on the rifle. Then he snapped a magazine holding forty pistol-sized .30 caliber cartridges into the device. This projected at an angle to the right of the rifle, allowing use of the standard sights. He then charged the device by pulling and releasing a heavy spring-loaded block on the back of it. He quickly proceeded to fire 40 shots as fast as he could pull the trigger.

The witnesses to this event were incredibly impressed, and the potential for the use of this invention in trench warfare was immediately recognized. Pederson called it an “automatic bolt” but almost immediately it became known as the Pedersen Device. It operated pretty much like a semiautomatic blowback pistol, but its framework was a slightly-altered Model 1903 rifle. The barrel of the device, which inserted into the chamber, was configured to the dimensions of the standard .30-06 cartridge case, and the small .30-caliber cartridge chambered in the breech of that barrel. This barrel within a barrel was rifled to start the bullet spinning down the regular rifled tube of the rifle. The rifle itself was slightly altered. It had an ejection port cut into the left side of the receiver, and the trigger mechanism was modified to allow both semiautomatic firing and the release of the firing mechanism in the standard bolt. The magazine was secured in place by two spring-loaded catches.

While the cartridges used were similar to .32 ACP pistol rounds, the bullets were .30 caliber, full metal jacketed, and weighed 80 grains. A charge of 3.5 grains of smokeless powder propelled the projectile at approximately 1300 feet per second, resulting in a muzzle energy of about 300 foot-pounds. That doesn’t sound like much, but being fired from a 24-inch barrel, it was way more powerful than similar rounds fired from a pistol. The device itself was carried on the belt in a special metal scabbard with belt hooks, and a web pouch was provided for the standard bolt when removed from the rifle. Two canvas magazine pouches held five magazines each, allowing a basic load of 400 rounds to be carried on the person. Each loaded magazine weighed about a pound, and the device itself weighed a little over two pounds. With rifles using these devices the trenches could easily be dominated with withering fire.

In November of 1917, a sample of the device was delivered by Captain J.C. Beatty to General John Pershing, the U.S. Army Expeditionary Force commander in France. Beatty was sworn to secrecy on the project; it was all classified as Top Secret. On December 9 of that year, General Pershing convened a board consisting of Capt. Beatty and four senior Ordnance officers. They tested the device for rate of fire, accuracy, penetration and reliability. Pershing was so impressed with the results of this test that he sent a memo to the Chief of Ordnance recommending an initial purchase of 100,000 of the devices and 5,000 rounds of ammunition per gun, providing a daily supply of 100 rounds per gun. He strongly believed it would do wonders for their efforts in France. Another memo soon followed, which stated “Desire 25,000 Pedersen attachments to be held in reserve. Replacements 50% per year on devices, and 200% on magazines. Request 40 magazines be shipped with each device. When will shipments be made? -Pershing.” Pershing was anticipating a huge offensive push in the spring of 1919, and wanted lots of these devices.

Because of its Top Secret classification, the device was given the intentionally misleading name of “Automatic Pistol, Caliber .30, Model of 1918, Mark I.” The ammo boxes were marked “40 – CAL. 30 AUTO, PISTOL / BALL CARTRIDGES / MODEL OF 1918” All the ammunition was produced by Remington-UMC, and so marked on the boxes. The production of this ammo caused some speculation and dismay in the press that the armed services were now using some sort of pipsqueak pistol to replace our Model 1911 .45 ACP handgun!

The eventual order placed with Remington was for 133,450 devices, and a contract was let for 800 million cartridges. These would be packed 40 to a box, each box enough to fill one magazine. Rock Island Arsenal produced the pouches for the bolt and magazines, and Graham Manufacturing Company made the scabbards for the device. Springfield Armory began manufacture of the modified ’03 rifle, which was dubbed the “U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, Model of 1903 Mark I.” As stated, the major differences from the regular ’03 were the ejection port, the trigger mechanism, the cutoff latch, and a stock relieved under the ejection port. Production of these rifles began in December 1918 and continued until March, 1920. 97,520 Mark I rifles were made, with serial numbers running from 933045 to 1186358. Most were finished in black Parkerizing, which had become the military standard.

World War I ended before any of the devices could be used in the war. A less hurried and more critical examination of the scheme revealed that the round was indeed quite underpowered, the equipment and ammo was heavy, and the potential for loss of the device and/or the bolt in the heat of battle was high. Some were actually used for gallery rifle practice and consideration was given to keeping them in reserve for riot control, but in April, 1931, an order was given to destroy all the devices and their accoutrements. Most were completely ruined in bonfires and then deep-sixed. A very few were stolen or salvaged to become incredibly expensive collector items today. Estimates vary on the number of surviving examples from a few dozen to as many as 100. The scabbards are even scarcer. The bolt and magazine pouches occasionally surface, but are fairly rare. A few “Mark II” devices, perhaps less than six, for the Model 1917 “Enfield” rifle are known. The Mark I rifles were almost all re-converted to standard ’03 specifications, and only a small number now remain in original device-ready condition. I’m fortunate enough to own one of these which left Springfield Armory in November of 1919. Today, a lot of people wonder about the hole in the side of the receiver when they encounter one, and the story behind that hole is still not widely known.

The Pedersen device was innovative, but became a dead end in firearms history. The devices and the rifles that used them are now very desirable classics. Few can afford one of the devices when and if one rarely becomes available on the collector market. The Mark I rifles can still be found here and there in varying conditions of originality. While not cheap, they’re considerably less expensive then the few remaining devices. There is a lot of history behind them.

(c) 2012 JLM

A pic of John D. Pedersen:

Some shots of the device and its ammo and accoutrements:

My own Mark I Springfield rifle:

Last edited: