This is another draft article for eventual publication in Dillon's Blue Press monthly catalog/magazine. As always, comments welcome.

John

The Winchester Model 1897 Trench Gun

This weapon was considered so deadly, unfair and frightful that for a while the World War I German high command threatened to summarily execute any Allied soldier who was captured wielding one. The Winchester Model 1897 pump-action 12-gauge trench shotgun could fire six double-aught buckshot shells (fifty-four .33 caliber balls in all) in about five seconds. This shotgun had no trigger disconnector mechanism, so it could be “slam fired” until its magazine was empty by holding the trigger back while rapidly and repeatedly shucking the action. It was easily one of the most devastating small arms available then or since. Add to this the fact that a bayonet could be mounted on it, and you had the perfect tool for mayhem in the trenches. The firestorm that these rapidly-fired shot shells could unleash spelled death in capital letters for any enemy encountered at short distance. This trench gun proved to be so effective that it was used throughout both World Wars I and II, the Korean War and even in Vietnam!

The Model 1897 was an improved Model 1893 pump shotgun, and both of these were designed by the immortal John Moses Browning. The ’97 was specifically designed for the somewhat longer than before 12 gauge 2 ¾” shell using smokeless powder. The top of the frame was covered so that the ejection of the fired shell was to the side. This gave more strength to the frame. The action was set up so that it could not be opened until a small forward movement of the slide handle released the slide lock. In firing, the recoil of the shotgun gave that motion to the slide handle automatically. A moveable cartridge guide was located on the right side of the carrier block to prevent inadvertently losing a shell when the shotgun was turned sideways when loading. Also, the stock was made longer than that on the Model 1893 and had less drop at the heel. It’s noteworthy that Winchester Model 1897s were produced from 1897 until 1957, when they were superseded at Winchester by the internal-hammered Model 12. In spite of being “obsolete,” sporting versions of the old ’97 are still popular and many remain in active use today.

Shorter 20-inch-barreled “riot” versions were used by our armed forces in limited numbers as early as 1900 to combat Philippine insurgents and then Mexican bandits on our border. After suitably modifying these basic riot guns with perforated-steel heat shields, sling swivels and bayonet mounts (calling these concoctions “trench guns”), thousands were ordered by the U.S. for the Great War in 1917. Already making bayonets for our Model 1917 Enfield rifles, Winchester created a special bayonet mount for the trench guns that would specifically take these blades. A bayonet, bayonet scabbard and sling were provided with each gun. A canvas sling pouch holding 32 all-brass shells was another useful accessory. The magazine tube on the Model 1897 held 5 shells, and with one in the chamber, six rounds would be available for instant use.

The Germans began to protest the use of this “trench sweeper” shotgun during WWI. In September of 1918, the German government lodged a diplomatic protest against the American use of shotguns, alleging that the shotgun was prohibited by the law of war. Part of the protest read “it is especially forbidden to employ arms, projections or materials calculated to cause unnecessary suffering” as defined in the 1907 Hague Convention on Land Warfare. The U.S. thought differently. The Judge Advocate General of the Army and the U.S. Secretary of State reviewed the law and formally rejected the German protest.

The U.S. response angered the Germans, who believed that they were treated unjustly. But by then in mid-1918, our trench guns were widely distributed and allocated 50 per division. Most of these went to scouting units who often made initial contact with the enemy. In reaction, the Germans threatened to execute U.S. soldiers who were captured with these guns. General John Pershing, the U.S. commander in WWI, counter-threatened that we would do the same with German soldiers who were captured with saw-backed bayonets or flame throwers. Both sides then quickly backed off of their threats, and the issue became moot. Shotguns continue to be used in combat regularly until the present day – they are well accepted.

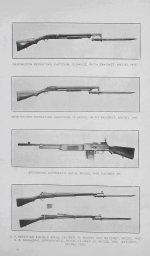

When World War II began, the U.S. quickly snapped up their remaining Model 1897s for use in the war, and ordered Winchester to manufacture many thousands more. These were in three configurations – trench, riot and training guns. While the WWI trench versions used a heat shield with six rows of ventilation holes, the WWII-era heat shields were specified to have four rows. Some Early WWII ‘97s were equipped with older-style 6-row shields. The gun illustrated here was produced by Winchester in early 1942, and has one of those 6-row shields. The WWII stocks were also slightly changed, and unlike their predecessors, these newer guns were all of takedown configuration to provide easier packing and shipping.

In WWII, each Marine regiment was allocated 100 Model ‘97s, and the Army continued to use them in varying roles. The Marines in the Pacific found both the old and new trench guns to be reliable, but had a real problem with commercial paper shells deteriorating in the humid climates. When the old-style brass shells were issued again, that problem was solved.

When WWII ended, more than 30,000 of these guns stayed in inventory, and when the Korean War broke out, they were pulled from storage and used yet again. They saw continued use in the Vietnam War, but new Model 1917-pattern bayonets (with plastic rather than wood grips) had to be produced to satisfactorily meet the demand.

Today, genuine Model 1897 trench guns of all vintages are incredibly valuable on the collector market. Be aware that many faked “put together” guns exist, and if authenticity is an issue, one should consult with a seasoned U.S. martial arms collector or refer to Bruce Canfield’s excellent book Complete Guide to US Combat Shotguns. It’s worth noting that none of these guns were originally issued with a Parkerized finish; all were blued from the factory. All number-stamped parts should match with the serial number. All of these trench guns of whatever vintage had cylinder-bore chokes, and should be marked on the barrel as such. With WWII guns, an inspection stamp in the stock reading “WB” (Lt. Col. Waldemar Broberg) or “GHD” (Brig. Gen. Guy H. Drewry) should be present. Factory-stamped U.S. markings in the metal should be there on early WWII guns, along with a “flaming bomb” stamp. Later ones may have only the “U.S.” stamp. WWI guns often had hand-stamped marks or none. Many of the First War guns were given to the South Vietnamese military in the 1960s and never repatriated, making them especially scarce.

To partially fill the demand by collectors for the genuine wartime weapons, a replica ’97 trench gun has been made by Norinco in China that usually sells for a few hundred dollars. However, reports are that the fit and finish of the replicas are not in keeping with the quality of the originals. Surviving genuine Winchester ’97 trench guns are in such demand that correct and complete examples are now going for well into multiple thousands of dollars. They are scarce U.S. military arms today, and are classic and important remnants of our 20th Century conflicts around the globe.

(c) 2018 JLM

John

The Winchester Model 1897 Trench Gun

This weapon was considered so deadly, unfair and frightful that for a while the World War I German high command threatened to summarily execute any Allied soldier who was captured wielding one. The Winchester Model 1897 pump-action 12-gauge trench shotgun could fire six double-aught buckshot shells (fifty-four .33 caliber balls in all) in about five seconds. This shotgun had no trigger disconnector mechanism, so it could be “slam fired” until its magazine was empty by holding the trigger back while rapidly and repeatedly shucking the action. It was easily one of the most devastating small arms available then or since. Add to this the fact that a bayonet could be mounted on it, and you had the perfect tool for mayhem in the trenches. The firestorm that these rapidly-fired shot shells could unleash spelled death in capital letters for any enemy encountered at short distance. This trench gun proved to be so effective that it was used throughout both World Wars I and II, the Korean War and even in Vietnam!

The Model 1897 was an improved Model 1893 pump shotgun, and both of these were designed by the immortal John Moses Browning. The ’97 was specifically designed for the somewhat longer than before 12 gauge 2 ¾” shell using smokeless powder. The top of the frame was covered so that the ejection of the fired shell was to the side. This gave more strength to the frame. The action was set up so that it could not be opened until a small forward movement of the slide handle released the slide lock. In firing, the recoil of the shotgun gave that motion to the slide handle automatically. A moveable cartridge guide was located on the right side of the carrier block to prevent inadvertently losing a shell when the shotgun was turned sideways when loading. Also, the stock was made longer than that on the Model 1893 and had less drop at the heel. It’s noteworthy that Winchester Model 1897s were produced from 1897 until 1957, when they were superseded at Winchester by the internal-hammered Model 12. In spite of being “obsolete,” sporting versions of the old ’97 are still popular and many remain in active use today.

Shorter 20-inch-barreled “riot” versions were used by our armed forces in limited numbers as early as 1900 to combat Philippine insurgents and then Mexican bandits on our border. After suitably modifying these basic riot guns with perforated-steel heat shields, sling swivels and bayonet mounts (calling these concoctions “trench guns”), thousands were ordered by the U.S. for the Great War in 1917. Already making bayonets for our Model 1917 Enfield rifles, Winchester created a special bayonet mount for the trench guns that would specifically take these blades. A bayonet, bayonet scabbard and sling were provided with each gun. A canvas sling pouch holding 32 all-brass shells was another useful accessory. The magazine tube on the Model 1897 held 5 shells, and with one in the chamber, six rounds would be available for instant use.

The Germans began to protest the use of this “trench sweeper” shotgun during WWI. In September of 1918, the German government lodged a diplomatic protest against the American use of shotguns, alleging that the shotgun was prohibited by the law of war. Part of the protest read “it is especially forbidden to employ arms, projections or materials calculated to cause unnecessary suffering” as defined in the 1907 Hague Convention on Land Warfare. The U.S. thought differently. The Judge Advocate General of the Army and the U.S. Secretary of State reviewed the law and formally rejected the German protest.

The U.S. response angered the Germans, who believed that they were treated unjustly. But by then in mid-1918, our trench guns were widely distributed and allocated 50 per division. Most of these went to scouting units who often made initial contact with the enemy. In reaction, the Germans threatened to execute U.S. soldiers who were captured with these guns. General John Pershing, the U.S. commander in WWI, counter-threatened that we would do the same with German soldiers who were captured with saw-backed bayonets or flame throwers. Both sides then quickly backed off of their threats, and the issue became moot. Shotguns continue to be used in combat regularly until the present day – they are well accepted.

When World War II began, the U.S. quickly snapped up their remaining Model 1897s for use in the war, and ordered Winchester to manufacture many thousands more. These were in three configurations – trench, riot and training guns. While the WWI trench versions used a heat shield with six rows of ventilation holes, the WWII-era heat shields were specified to have four rows. Some Early WWII ‘97s were equipped with older-style 6-row shields. The gun illustrated here was produced by Winchester in early 1942, and has one of those 6-row shields. The WWII stocks were also slightly changed, and unlike their predecessors, these newer guns were all of takedown configuration to provide easier packing and shipping.

In WWII, each Marine regiment was allocated 100 Model ‘97s, and the Army continued to use them in varying roles. The Marines in the Pacific found both the old and new trench guns to be reliable, but had a real problem with commercial paper shells deteriorating in the humid climates. When the old-style brass shells were issued again, that problem was solved.

When WWII ended, more than 30,000 of these guns stayed in inventory, and when the Korean War broke out, they were pulled from storage and used yet again. They saw continued use in the Vietnam War, but new Model 1917-pattern bayonets (with plastic rather than wood grips) had to be produced to satisfactorily meet the demand.

Today, genuine Model 1897 trench guns of all vintages are incredibly valuable on the collector market. Be aware that many faked “put together” guns exist, and if authenticity is an issue, one should consult with a seasoned U.S. martial arms collector or refer to Bruce Canfield’s excellent book Complete Guide to US Combat Shotguns. It’s worth noting that none of these guns were originally issued with a Parkerized finish; all were blued from the factory. All number-stamped parts should match with the serial number. All of these trench guns of whatever vintage had cylinder-bore chokes, and should be marked on the barrel as such. With WWII guns, an inspection stamp in the stock reading “WB” (Lt. Col. Waldemar Broberg) or “GHD” (Brig. Gen. Guy H. Drewry) should be present. Factory-stamped U.S. markings in the metal should be there on early WWII guns, along with a “flaming bomb” stamp. Later ones may have only the “U.S.” stamp. WWI guns often had hand-stamped marks or none. Many of the First War guns were given to the South Vietnamese military in the 1960s and never repatriated, making them especially scarce.

To partially fill the demand by collectors for the genuine wartime weapons, a replica ’97 trench gun has been made by Norinco in China that usually sells for a few hundred dollars. However, reports are that the fit and finish of the replicas are not in keeping with the quality of the originals. Surviving genuine Winchester ’97 trench guns are in such demand that correct and complete examples are now going for well into multiple thousands of dollars. They are scarce U.S. military arms today, and are classic and important remnants of our 20th Century conflicts around the globe.

(c) 2018 JLM

Last edited: