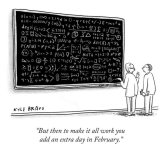

Any of us been wondering about this recently?

To tame a hopelessly disorganised Roman calendar, Julius Caesar added months, took them away, and invented leap years. But the whole grand project was almost thwarted by a basic counting mistake.

BBC article here. You'll have to read the entire article to try and get your head around all this, but here are a few excerpts:

To tame a hopelessly disorganised Roman calendar, Julius Caesar added months, took them away, and invented leap years. But the whole grand project was almost thwarted by a basic counting mistake.

BBC article here. You'll have to read the entire article to try and get your head around all this, but here are a few excerpts:

Welcome to 46BC, better known as the Year of Confusion.

...It was confusing enough when the harvest celebrations kept arriving in the middle of spring. It was the 1st Century BC and, according to ritual, there ought to be ripe vegetables ready for eating. But to any farm labourer looking around in the field, it was clear there would be many months before the harvest.

The problem was the early Roman calendar, which had become so unruly that crucial annual festivals bore increasingly little resemblance to what was going on in the real world...

...The early Roman calendar was determined by the cycles of the Moon and the cycles of the agricultural year. Looking at this calendar with modern eyes, you might feel a bit short-changed. There are only 10 months in it, starting in March in spring, and the tenth and final month of the year is what we now know as December. Six of those months had 30 days, and four had 31 days – giving a total of 304 days. What about the rest?

"For the two months of the year when there's no work being done in the field, they're just not counted," says Parish. The Sun rises and falls but, according to the early Roman calendar, no day has officially passed...

(Talk about a Protestant wotk ethic! No work done= no day!)...It was confusing enough when the harvest celebrations kept arriving in the middle of spring. It was the 1st Century BC and, according to ritual, there ought to be ripe vegetables ready for eating. But to any farm labourer looking around in the field, it was clear there would be many months before the harvest.

The problem was the early Roman calendar, which had become so unruly that crucial annual festivals bore increasingly little resemblance to what was going on in the real world...

...The early Roman calendar was determined by the cycles of the Moon and the cycles of the agricultural year. Looking at this calendar with modern eyes, you might feel a bit short-changed. There are only 10 months in it, starting in March in spring, and the tenth and final month of the year is what we now know as December. Six of those months had 30 days, and four had 31 days – giving a total of 304 days. What about the rest?

"For the two months of the year when there's no work being done in the field, they're just not counted," says Parish. The Sun rises and falls but, according to the early Roman calendar, no day has officially passed...

In 731BC, the second King of Rome, Numa Pompilius, decided to improve the calendar by introducing extra months to cover that winter period... Pompilius' answer was to add 51 days to the calendar, creating what we now call January and February. This extension brought the calendar year up to 355 days.

If 355 days seems like an odd number for Pompilius to aim for, that was on purpose. The number takes its reference from the lunar year (12 lunar months), which is 354 days long. However, "because of Roman superstitions about even numbers, an additional day is added to make 355"...

By around 200BC things had got sufficiently bad that a near-total eclipse of the Sun was observed in Rome on what we would now consider to be 14 March, but is recorded as having taken place on 11 July.

Because the calendar had by this point gone "so catastrophically wrong", Parish says, the Emperor and priests in Rome resorted to inserting an additional "intercalary" month, Mercedonius, on an ad-hoc basis to try to realign the calendar to the seasons...

Enter Sosigenes, who had a solution..If 355 days seems like an odd number for Pompilius to aim for, that was on purpose. The number takes its reference from the lunar year (12 lunar months), which is 354 days long. However, "because of Roman superstitions about even numbers, an additional day is added to make 355"...

By around 200BC things had got sufficiently bad that a near-total eclipse of the Sun was observed in Rome on what we would now consider to be 14 March, but is recorded as having taken place on 11 July.

Because the calendar had by this point gone "so catastrophically wrong", Parish says, the Emperor and priests in Rome resorted to inserting an additional "intercalary" month, Mercedonius, on an ad-hoc basis to try to realign the calendar to the seasons...

...it would have worked quite well, at least for a while, if there hadn't been the problem of the idiosyncratic way the Romans counted the years."They look at the years and they count, one, two, three, four," says Parish. "And then they start counting again at four – so they count four, five, six, seven. Then they start at seven – so seven, eight, nine, 10. So they're accidentally double-counting one of those years each time...

... around the middle of the 56th Century, "somebody is going to scratch their head and say, 'Hang on a minute, it should be Monday, but it's actually looking like Tuesday'," says Parish. "I think that's probably a margin of error that we're going to end up accepting."

Until that Monday (or Tuesday), the Gregorian calendar has at least bought us a bit of time.

Of course, if they'd had iPhones (or slide rules), none of this would likely have happened ... around the middle of the 56th Century, "somebody is going to scratch their head and say, 'Hang on a minute, it should be Monday, but it's actually looking like Tuesday'," says Parish. "I think that's probably a margin of error that we're going to end up accepting."

Until that Monday (or Tuesday), the Gregorian calendar has at least bought us a bit of time.