Again, a sneak peek at a future article. Always glad to get comments and constructive criticism. Hope you enjoy it.

John

The Winchester Model 63

It’s been described by many experts as the best .22 rimfire autoloading rifle that Winchester ever made, and perhaps the best ever made, period. Certainly the Winchester Model 63 was made to the old exacting standards – forged and milled steel, handsome walnut, careful fitting and finishing and great reliability and accuracy. Today’s manufacturing methods and materials have certainly resulted in guns being made more cheaply, but for a lot of people, nothing will ever equal the old-time Winchester quality exhibited in the Model 63. These rifles have been out of print for a long time, but collectors still salivate over them when good used examples come on the market.

For a bit of history, we have to go back to the 1890s. Although John Browning and Winchester had collaborated on many fine guns, there was a falling out between them when Winchester refused to sign a per-gun royalty agreement on a new semiautomatic shotgun design. Browning then went to Fabrique Nationale in Belgium, who immediately saw the merits of the gun and subsequently produced it as the Browning Auto 5. Remington also sought Browning out and secured the U.S. rights to the gun as the Remington Model 11.

Because of this unfortunate friction with Browning, Winchester was left with only its internal staff to design its first semiauto sporting rifle. This was a new and untried concept, as nothing like it had been invented or produced before. Luckily for them, they had a crack team of gifted people who were up to the challenge. In 1891, Winchester tasked William Mason and Thomas C. Johnson to begin preliminary research on various operating systems. Johnson, who had been with Winchester since 1885, came up with a system where a relatively light bolt was attached to a heavier slide located within the forestock of the rifle. The weight of the slide and the bolt, together with the pressure of the recoil spring and resistance of the internal hammer could counterbalance the modest recoil of a .22 rimfire cartridge. In this way the bullet would have already left the barrel before the bolt started to open. This concept was later known as the blowback principle, but at the time had been utilized only in rather low-powered pistols. The recoil spring then returned the bolt into battery and picked up a new round from the tubular magazine in the stock. Initial manual operation of the bolt was through a spring-loaded push-back rod located in the nose of the forestock. The bolt did not catch to the rear after the last shot was fired. When the internal spring-loaded magazine follower tube was rotated counter-clockwise in the butt, it could be pulled back. This exposed the cartridge loading port on the right side of the buttstock. As many as 10 rounds were loaded there one by one, nose first. The internal follower tube was then pressed forward and locked into place with a clockwise turn. This pressed the loaded rounds forward for feeding by the bolt into the chamber.

Although the .22 Long Rifle cartridge had been available since 1887, there were no standards at the time for the power level or propellant for that cartridge. Some rounds were still loaded with black powder, which left too much residue in the barrel and action. The blowback action of the gun invented by Johnson relied on a uniform recoil impulse for the action to operate reliably. Accordingly, Winchester designed a special .22 rimfire cartridge for the new gun, known as the “.22 Winchester Automatic Rimfire Smokeless.” Unlike the .22 LR, it did not utilize a heeled bullet – the shank of the bullet entered the case, which was larger in diameter to accommodate it.

The Model 1903 was introduced chambered for that round, and it was an immediate hit with the public. It was the first commercially manufactured semiautomatic rifle. This was a take-down design which enabled the gun to be separated into two main assemblies for ease of transportation. A screw at the rear of the frame could be loosened, and the barrel and bolt group could be pulled away, separating it from the buttstock and trigger-hammer group. While very early production guns lacked any sort of safety, a cross-bolt safety in the rear of the trigger guard was soon added. Standard models had a straight grip buttstock, while deluxe models with a pistol grip were an option. A 20” round barrel was standard on all guns. The Model 1903 was produced to the tune of about 126,000 units. It was the favorite gun of legendary exhibition shooter Ad Topperwein. He used it to shoot at 72,500 hand-thrown wooden blocks in 1907, missing only nine. This record stood for over 50 years. The Model 1903 paved the way for a similar centerfire version, the Model 1905 Self-Loading Rifle.

As smokeless powder became more of a standard for the .22 LR cartridge, Remington stole the march with the Browning-designed Model 24 autoloading rifle that could handle that round. Winchester was faced with the fact that their proprietary cartridge was not selling in the numbers now commanded by the .22 LR. They needed to re-design their renamed Model 03 to work with the more popular ammunition. They were a bit slow to do this, but the gun that followed was a winner. In 1933, the Model 63 was introduced, specifically designed to handle Winchester Super Speed and Super-X .22 LR cartridges. The barrels of these guns were marked to specify these particular high-speed loads. Early production guns had 20” round barrels, but in 1934, 23” round barrels were offered as an option. The latter length became popular enough that the 20” barrel was discontinued in 1936. The early takedown screw at the rear of the action was copied directly from the Model 03 in first production, but was improved for easier manipulation shortly after introduction. The rifle illustrated is a 1935 example with the 23” barrel.

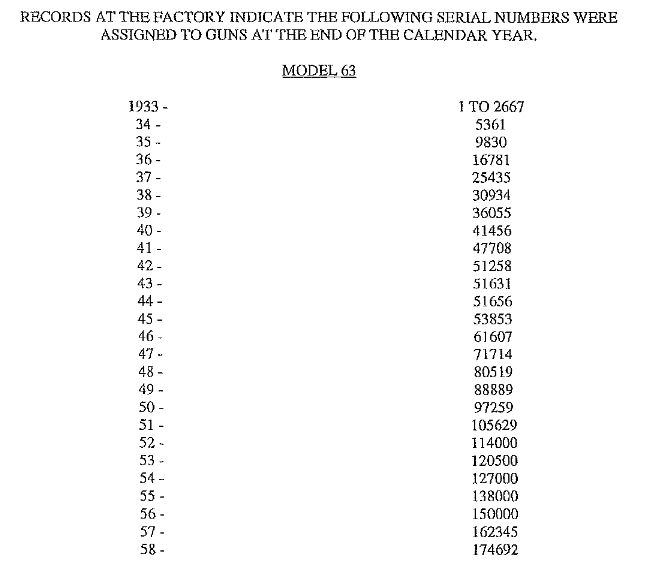

Very few changes were made in the following years. All Model 63s had 10-round magazines, pistol grips, and plain walnut furniture throughout production. The barrel’s date of manufacture was usually stamped underneath the barrel near the receiver. To date any specific gun, reference charts of the years of manufacture cross-referenced with serial numbers can be found readily on the internet. The World War II years brought a virtual halt to the production of the Model 63 and other sporting rifles. Just a few were assembled as Winchester devoted almost all of its resources to the war effort. The 63 was brought back in quantity after the war in 1946. The only significant change was that in 1958, about 10,000 guns were grooved for tip-off scope mounting. Special order guns with fancy wood and checkering exist. Due to increased production costs that made further manufacturing of the Model 63 impractical by the old methods, the gun was discontinued. The 1958 Winchester catalog was the last to offer it. In all, 174,692 of these guns were produced.

There continued to be a pent-up demand for the Model 63, and the prices of used guns continued to rise when they were found at gun shows and gun stores. As a result, finally in 1997, Winchester authorized a reproduction of the gun made in Japan. There are some internal and external differences in these newer guns, but they mimic the look, feel and operation of the originals, with good quality. Taurus has also made what they call a Model 63 at an attractive price, but it is not quite as true to the originals, being made with modern manufacturing materials and methods.

The gun itself has some quirks. First, because the rear of the frame blocks access to the barrel from the rear with a cleaning rod, the gun can’t be cleaned that way. The boss that receives the takedown screw is the interfering culprit, and it’s an integral part of the frame. In addition, the Model 63 is a bit difficult to disassemble to the point of bolt removal. The factory only suggests that taking it down into the two major assemblies is sufficient to expose most of the parts for cleaning. There are only two ways to clean the barrel – with a rod inserted down the muzzle, or with a pull-through thong that will draw a brush or patch through the barrel from the breech end. The second method is more satisfactory, as there is then little chance of damaging the lands and grooves at the muzzle and degrading accuracy.

Those who have not read some instructions on the gun will also wonder how the bolt can be held to the rear for safety or ease of cleaning. That procedure is less than intuitive. When the operating rod forward of the forestock is pressed almost fully rearward to open the bolt, the cap on the rod can be twisted clockwise to lock the bolt open. This cap is thin, the rod is under heavy spring pressure, and if one isn’t careful, it’s easy to hurt the thumb and finger. One solution offered by long-time users was to cut a piece of wood to the width of the ejection port, retract the bolt, then jam the piece of wood in the opening to hold the bolt almost all the way back. Then the cap of the operating rod can be twisted with ease to lock the bolt back. Needless to say, carrying such a piece of wood around with the rifle will seem odd to many folks.

Collectors are now willing to pay a pretty penny for decent Model 63s. The ones grooved for scope mounting are considered particularly desirable and worth a premium. This classic gun lives on with modern production for Winchester in Japan, as the demand for it has never slacked.

(c) 2015 JLM

John

The Winchester Model 63

It’s been described by many experts as the best .22 rimfire autoloading rifle that Winchester ever made, and perhaps the best ever made, period. Certainly the Winchester Model 63 was made to the old exacting standards – forged and milled steel, handsome walnut, careful fitting and finishing and great reliability and accuracy. Today’s manufacturing methods and materials have certainly resulted in guns being made more cheaply, but for a lot of people, nothing will ever equal the old-time Winchester quality exhibited in the Model 63. These rifles have been out of print for a long time, but collectors still salivate over them when good used examples come on the market.

For a bit of history, we have to go back to the 1890s. Although John Browning and Winchester had collaborated on many fine guns, there was a falling out between them when Winchester refused to sign a per-gun royalty agreement on a new semiautomatic shotgun design. Browning then went to Fabrique Nationale in Belgium, who immediately saw the merits of the gun and subsequently produced it as the Browning Auto 5. Remington also sought Browning out and secured the U.S. rights to the gun as the Remington Model 11.

Because of this unfortunate friction with Browning, Winchester was left with only its internal staff to design its first semiauto sporting rifle. This was a new and untried concept, as nothing like it had been invented or produced before. Luckily for them, they had a crack team of gifted people who were up to the challenge. In 1891, Winchester tasked William Mason and Thomas C. Johnson to begin preliminary research on various operating systems. Johnson, who had been with Winchester since 1885, came up with a system where a relatively light bolt was attached to a heavier slide located within the forestock of the rifle. The weight of the slide and the bolt, together with the pressure of the recoil spring and resistance of the internal hammer could counterbalance the modest recoil of a .22 rimfire cartridge. In this way the bullet would have already left the barrel before the bolt started to open. This concept was later known as the blowback principle, but at the time had been utilized only in rather low-powered pistols. The recoil spring then returned the bolt into battery and picked up a new round from the tubular magazine in the stock. Initial manual operation of the bolt was through a spring-loaded push-back rod located in the nose of the forestock. The bolt did not catch to the rear after the last shot was fired. When the internal spring-loaded magazine follower tube was rotated counter-clockwise in the butt, it could be pulled back. This exposed the cartridge loading port on the right side of the buttstock. As many as 10 rounds were loaded there one by one, nose first. The internal follower tube was then pressed forward and locked into place with a clockwise turn. This pressed the loaded rounds forward for feeding by the bolt into the chamber.

Although the .22 Long Rifle cartridge had been available since 1887, there were no standards at the time for the power level or propellant for that cartridge. Some rounds were still loaded with black powder, which left too much residue in the barrel and action. The blowback action of the gun invented by Johnson relied on a uniform recoil impulse for the action to operate reliably. Accordingly, Winchester designed a special .22 rimfire cartridge for the new gun, known as the “.22 Winchester Automatic Rimfire Smokeless.” Unlike the .22 LR, it did not utilize a heeled bullet – the shank of the bullet entered the case, which was larger in diameter to accommodate it.

The Model 1903 was introduced chambered for that round, and it was an immediate hit with the public. It was the first commercially manufactured semiautomatic rifle. This was a take-down design which enabled the gun to be separated into two main assemblies for ease of transportation. A screw at the rear of the frame could be loosened, and the barrel and bolt group could be pulled away, separating it from the buttstock and trigger-hammer group. While very early production guns lacked any sort of safety, a cross-bolt safety in the rear of the trigger guard was soon added. Standard models had a straight grip buttstock, while deluxe models with a pistol grip were an option. A 20” round barrel was standard on all guns. The Model 1903 was produced to the tune of about 126,000 units. It was the favorite gun of legendary exhibition shooter Ad Topperwein. He used it to shoot at 72,500 hand-thrown wooden blocks in 1907, missing only nine. This record stood for over 50 years. The Model 1903 paved the way for a similar centerfire version, the Model 1905 Self-Loading Rifle.

As smokeless powder became more of a standard for the .22 LR cartridge, Remington stole the march with the Browning-designed Model 24 autoloading rifle that could handle that round. Winchester was faced with the fact that their proprietary cartridge was not selling in the numbers now commanded by the .22 LR. They needed to re-design their renamed Model 03 to work with the more popular ammunition. They were a bit slow to do this, but the gun that followed was a winner. In 1933, the Model 63 was introduced, specifically designed to handle Winchester Super Speed and Super-X .22 LR cartridges. The barrels of these guns were marked to specify these particular high-speed loads. Early production guns had 20” round barrels, but in 1934, 23” round barrels were offered as an option. The latter length became popular enough that the 20” barrel was discontinued in 1936. The early takedown screw at the rear of the action was copied directly from the Model 03 in first production, but was improved for easier manipulation shortly after introduction. The rifle illustrated is a 1935 example with the 23” barrel.

Very few changes were made in the following years. All Model 63s had 10-round magazines, pistol grips, and plain walnut furniture throughout production. The barrel’s date of manufacture was usually stamped underneath the barrel near the receiver. To date any specific gun, reference charts of the years of manufacture cross-referenced with serial numbers can be found readily on the internet. The World War II years brought a virtual halt to the production of the Model 63 and other sporting rifles. Just a few were assembled as Winchester devoted almost all of its resources to the war effort. The 63 was brought back in quantity after the war in 1946. The only significant change was that in 1958, about 10,000 guns were grooved for tip-off scope mounting. Special order guns with fancy wood and checkering exist. Due to increased production costs that made further manufacturing of the Model 63 impractical by the old methods, the gun was discontinued. The 1958 Winchester catalog was the last to offer it. In all, 174,692 of these guns were produced.

There continued to be a pent-up demand for the Model 63, and the prices of used guns continued to rise when they were found at gun shows and gun stores. As a result, finally in 1997, Winchester authorized a reproduction of the gun made in Japan. There are some internal and external differences in these newer guns, but they mimic the look, feel and operation of the originals, with good quality. Taurus has also made what they call a Model 63 at an attractive price, but it is not quite as true to the originals, being made with modern manufacturing materials and methods.

The gun itself has some quirks. First, because the rear of the frame blocks access to the barrel from the rear with a cleaning rod, the gun can’t be cleaned that way. The boss that receives the takedown screw is the interfering culprit, and it’s an integral part of the frame. In addition, the Model 63 is a bit difficult to disassemble to the point of bolt removal. The factory only suggests that taking it down into the two major assemblies is sufficient to expose most of the parts for cleaning. There are only two ways to clean the barrel – with a rod inserted down the muzzle, or with a pull-through thong that will draw a brush or patch through the barrel from the breech end. The second method is more satisfactory, as there is then little chance of damaging the lands and grooves at the muzzle and degrading accuracy.

Those who have not read some instructions on the gun will also wonder how the bolt can be held to the rear for safety or ease of cleaning. That procedure is less than intuitive. When the operating rod forward of the forestock is pressed almost fully rearward to open the bolt, the cap on the rod can be twisted clockwise to lock the bolt open. This cap is thin, the rod is under heavy spring pressure, and if one isn’t careful, it’s easy to hurt the thumb and finger. One solution offered by long-time users was to cut a piece of wood to the width of the ejection port, retract the bolt, then jam the piece of wood in the opening to hold the bolt almost all the way back. Then the cap of the operating rod can be twisted with ease to lock the bolt back. Needless to say, carrying such a piece of wood around with the rifle will seem odd to many folks.

Collectors are now willing to pay a pretty penny for decent Model 63s. The ones grooved for scope mounting are considered particularly desirable and worth a premium. This classic gun lives on with modern production for Winchester in Japan, as the demand for it has never slacked.

(c) 2015 JLM

Last edited: