Estonia’s Independence, Finland’s Role in Establishing and Training the Estonian Defense Forces and Kaitseliit, and the Most Significant Equipment Donations

Estonia’s Independence (1918–1920)

Estonia’s path to independence began with the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917. In February 1918, Estonia declared independence, but German forces soon occupied the country. After Germany’s defeat in World War I in November 1918, Estonia seized a new opportunity for sovereignty. However, Soviet Russia invaded late that year, sparking the Estonian War of Independence (1918–1920). Estonia fought against Bolsheviks, and the withdrawal of German troops left behind pro-German factions, such as supporters of the Baltic Duchy, complicating the situation. The war ended in Estonia’s victory, and the Treaty of Tartu (February 2, 1920) confirmed its independence.

Estonia established a provisional government in 1917, with Konstantin Päts as its first prime minister. After the independence declaration (February 24, 1918), Estonia began building its defense forces, but resources were scarce. Finland’s support was critical, as it had recently undergone its own independence process and civil war in 1918, giving it experience and a willingness to aid Estonia.

Finland’s Role in Establishing Estonia’s Defense Forces

Finland supported Estonia in numerous ways during and after the War of Independence, particularly in establishing the Estonian Defense Forces (Eesti Kaitsevägi) and Kaitseliit (Estonia’s voluntary defense organization, analogous to Finland’s Civil Guard). Finland’s assistance was both material and educational, as well as logistical.

Volunteers and Military Support in the War of Independence

Finnish Volunteers: Approximately 3,500–4,000 Finnish volunteers fought in Estonia’s War of Independence, forming units like the Pohjan Pojat (Sons of the North) and others. Led by Colonel Martin Wetzer, they participated in key battles, such as those at Narva and the Paju-Tartu line in 1919. The Finns brought experience from Finland’s Civil War, particularly the tactics of the White forces.

Tactical Expertise: Finns taught Estonians guerrilla tactics, fortification techniques, and small-unit combat, which had proven effective in Finland’s Civil War. This was vital, as Estonia’s army initially consisted of poorly organized volunteers with little training.

Organizing the Defense Forces

Estonia’s Defense Forces were formally established in 1918, but their development began in earnest after the war. Finland assisted in creating officer training programs and military structures. Finnish officers, such as Colonel Hans Kalm, served as advisors and trainers.

Estonia’s first military commander, General Johan Laidoner, drew on Finland’s experience with the Civil Guard model and officer education. Though trained in Russia, Laidoner valued Finland’s practical approach.

Establishing and Training Kaitseliit

Kaitseliit was founded in 1918, modeled on Finland’s Civil Guard, which had proven its worth in Finland’s Civil War. Finnish Civil Guard activists, such as Vihtori Kosola and Lauri Pihkala, visited Estonia to share knowledge on organization, training, and operations.

Kaitseliit’s training emphasized volunteers’ military readiness, rifle marksmanship, and patriotic spirit. Finns helped develop training programs and organize local units, especially in rural areas.

Kaitseliit also took on a societal role, such as fostering patriotic education among youth, drawing inspiration from Finland. For example, Estonia’s youth military training (Noored Kotkad) was influenced by Finland’s youth Civil Guard programs.

Most Significant Equipment Donations

Finland donated and supplied significant military equipment to Estonia during and after the War of Independence. These donations were critical, as Estonia lacked its own arms industry, and its stockpiles consisted mainly of outdated Russian and German equipment.

Rifles and Light Weapons

Finland donated thousands of rifles, primarily Russian Mosin-Nagant M1891 models, left over from Finland’s Civil War. Estimates suggest 10,000–20,000 rifles were provided in 1918–1919.

Additionally, Finland supplied machine guns, such as the Maxim M/09-21, which were effective in defensive positions.

Artillery

Finland donated several field guns, particularly Russian 76 mm and 122 mm howitzers, sourced from Russian army stockpiles. Dozens of these guns formed the backbone of Estonia’s artillery.

For coastal defense, Finland provided smaller 75 mm and 120 mm guns, which supported the protection of Estonian ports like Tallinn and Paldiski.

Naval Equipment

Finland aided Estonia’s navy by donating smaller vessels, such as patrol boats and minesweepers, sourced from abandoned Russian Baltic Fleet stocks. In 1919, Finland transferred at least two smaller vessels, which were renamed in Estonian service.

Finland also trained Estonian naval personnel, particularly in minesweeping and coastal defense.

Other Supplies

Finland provided uniforms, backpacks, field telephones, and other logistical equipment essential for outfitting Estonia’s army. For instance, surplus Civil Guard gear, such as boots and tents, was sent to Estonia.

Hundreds of thousands of rounds of ammunition (for rifles, machine guns, and artillery) were delivered, crucial as the war dragged on.

Impact of Equipment Donations

War of Independence: Donated rifles and artillery enabled Estonia to equip its forces and rapidly develop combat capability. Without Finland’s aid, Estonia would have been more vulnerable to Bolshevik attacks.

Long-Term Impact: The donations laid the foundation for Estonia’s Defense Forces and Kaitseliit, which maintained independence until the Soviet occupation in 1940. Artillery and naval vessels, for example, were used in the 1930s to protect Estonia’s fortifications and ports.

Cultural Bond: Equipment donations and training strengthened solidarity between Finland and Estonia, evident in later collaborations, such as planning the Gulf of Finland artillery blockade.

Challenges and Limitations

Finland’s own resources were limited after its Civil War, so donations did not always meet Estonia’s needs in quantity.

Some equipment, particularly Russian artillery, was outdated and required maintenance or modernization.

Logistical challenges, such as transporting supplies across the sea, occasionally delayed aid, especially during the war’s most intense phases.

Estonia’s Re-independence in the 1990s

Estonia restored its independence on August 20, 1991, amid the Soviet Union’s collapse. The process began in the late 1980s, enabled by Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost, which gave rise to a national awakening. The Singing Revolution (1987–1991), marked by massive song festivals and human chains, united Estonians in their demand for independence. The failed Moscow coup in August 1991 weakened Soviet central authority, prompting Estonia’s Supreme Council to declare the restoration of independence. Finland swiftly recognized Estonia’s independence on August 25, 1991, and diplomatic relations were re-established. Soviet troops fully withdrew from Estonia by 1994.

Finland’s Role in Establishing and Training the Estonian Defence Forces and Kaitseliit

Estonian Defence Forces:

At the time of independence, Estonia’s Defence Forces (Eesti Kaitsevägi) were virtually non-existent, as the Soviet military had controlled the region. Finland played a significant role in their reconstruction during the 1990s, though official support was initially cautious due to concerns about Russia’s reaction.

1992–1994: Approximately 90 retired Finnish officers and reservists voluntarily assisted in developing Estonia’s Defence Forces at their own expense. They helped with training and organizational setup, drawing on Finland’s conscription model.

1996 onward: Official cooperation began when Estonia’s Defence Forces commander, Johannes Kert, requested Finland’s assistance. Lieutenant General Pentti Lehtimäki coordinated the project, focusing on training. From 1996 to 2003, around 450 Estonian soldiers were trained in Finland, including 21 officers (e.g., Tarmo Kõuts and Johannes Kert) who attended specialized courses. Estonian conscripts also trained at Finland’s Reserve Officer School.

Training emphasized Finland’s model of independent, small, and mobile units, contrasting with the Soviet army’s massive structure. Estonian officers like Andrus Merilo and Ilmar Tamm studied in Finland, bringing Finnish expertise to Estonia’s system and strengthening military cooperation.

Kaitseliit:

Kaitseliit, Estonia’s voluntary defense organization, was re-established in 1990, continuing its 1918 legacy after being disbanded by the Soviets in 1940.

Finland indirectly influenced Kaitseliit’s development, as its original 1930s model was inspired by Finland’s Civil Guard (Suojeluskunta). In the 1990s, Finnish reservists contributed to training, particularly in tactics and leadership.

Kaitseliit was integrated into the Defence Forces in April 1992, and its training drew on Finnish experience. However, Finland lacked a direct equivalent to Kaitseliit, so the U.S. Maryland National Guard provided the most significant support for its development.

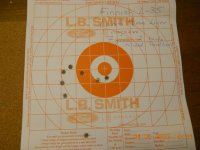

Finnish assistance focused on marksmanship training, leveraging Kaitseliit’s historical network of shooting ranges, which was the densest in the world in the 1930s, to revive this tradition.

Most Significant Equipment Donations

Finland donated relatively modest amounts of materiel compared to countries like the U.S. or Germany, but these contributions were vital for Estonia’s early defense capabilities:

Field Artillery: 19 lightweight 105 mm field guns with ammunition, forming the backbone of two artillery batteries.

Mortars: 54 mortars, enhancing infantry fire support.

Anti-Aircraft Guns: 100 23 mm anti-aircraft guns, critical for early air defense.

Other Equipment: Fire control and communication gear, engineering tools, training equipment, barracks furnishings, kitchen supplies, and air force materiel such as radio equipment and flight gear.

These donations were highly valued, as Estonia’s Defence Forces had almost no heavy equipment in 1991, and Soviet-era materiel was often disorganized or obsolete. The donations provided a foundation for basic capabilities, though Estonia later required modern equipment to meet NATO standards.

Estonia regained independence in August 1991 through the Singing Revolution and the Soviet Union’s collapse. Finland cautiously but significantly supported the development of Estonia’s Defence Forces and Kaitseliit, primarily through training: 450 Estonians were trained in Finland from 1996 to 2003, and Finnish officers and reservists shared expertise starting in 1992. Kaitseliit’s development partly drew on Finland’s model, though

the U.S. was its main supporter. Key equipment donations included 19 field guns, 54 mortars, and 100 anti-aircraft guns, laying the groundwork for Estonia’s defense capabilities. Finland’s assistance was crucial in the early stages of Estonia’s military rebuilding, even if much of it occurred behind the scenes.