Hi all,

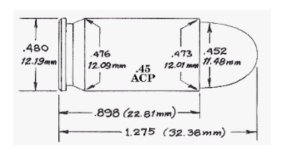

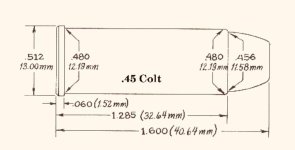

I add some meat to the fire, that is, some other document. The letter of August 20, 1874 departed from the Ordnance Office bound for Frankford Arsenal, signed by the Principal Assistant to the Chief of Ordnance, Lieutenant George W. McKee. As reported in the book by C. Kenneth Moore, the sentence concerning the size of the chambers is not there and it seems strange that a precise and fussy historian like C. Kenneth Moore does not report such an important passage, since he does not neglect even apostrophes. I cover it exactly as it is in the book: «I am instructed by the Chief of Ordnance to direct you to stop the manufacture of the Colt's revolver cartridges Cal. 45. The Com'd'g. Officer National Armory will send you a sample cartridge intended for both Colt's and Smith & Wesson's revolvers. When received at your post you will proceed to manufacture one million of them. The special designation of the labels therefore will be determined thereafter.»

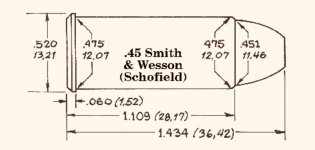

But apart from this detail it should be noted that the communication was born from a kilometric letter from George W. Scofield of August 5, 1874 addressed to the Chief of Ordnance. Schofield, in addition to complaining because he had been asked for the change from the .44 caliber to the .45 caliber, went on to criticize the very system of the .45 cartridge supplied for a year, that is, the "Cartridge for Colt's revolver". In this letter from Schofield there is no reference to the bore of the barrels and cylinders of the two arms Colt and Smith & Wesson. Instead, he talks about the length of the cartridge and its rim too small for effective extraction with the Smith & Wesson extractor star. Evidently he could not yet talk about the size of the chambers and barrels since at that time the Smith & Wesson just tested was still in .44 caliber. But he talks about the cartridge.

And he wrote to the Chief of Ordnance:« .. It is found, that even with so long a cylinder it is not necessary to use so long a cartridge as that now issued with the Colt pistol and that a better cartridge even can be made for that pistol and one which can at the same time be ejected by the more approved mode of acting on the heads of rims. Sample of such a cartridge will, I understand, be forwarded to you tomorrow. In a trial today, at the National Armory, in the presence of Col. Benton (Arsenal Commander), better results were obtained from Colt's pistol firing this new cartridge than when firing the regular Colt cartridge.» Then on August 5, 1874, in the presence of the Commander of the Springfield Arsenal, a cartridge designed for a Smith Wesson, still in caliber 44 and therefore not yet built, had been fired on the Colt. So, if on that date there was already a cartridge that worked well on the Colt, how can we think that a few months later a Smith Wesson was born with a chamber not compatible with that cartridge? Here is my question!

C. Kenneth Moore then states that he did not find any other documents in the National Archives concerning this subject until February 1875. On February 18, 1875, the commander of the National Armory, Benton, sent a Colt's Army Revolver and a Schofield Smith & Wesson to Frankford Arsenal and a letter: « .. I also send standard and limit gauges, for the cartridge shell which are adapted for both weapons. no gauges are furnished for the bullet but samples are furnished of the best form of bullet to provide against the front end of bullet projecting beyond the front surface of the cylinder, in case it should be thrown out of shell by recoil of the pistol. This was found to be a likely circumstance where the short S&W cartridge is used in the Colt revolver, and the bullet is not made as blunt as that I furnish you. The condition requiring that the bullet should weigh but 230 grains necessitated deepenning the cavity in the base and you may find it essential to increase the powder charge from 28 to 30 grains in order to fill the space.»

Giorgio